Ways to Restrict the Use of the Death Penalty in Iran

Statistics

READ THE FULL REPORT HERE (pdf)

Read the article on the Iran Human Rights website here

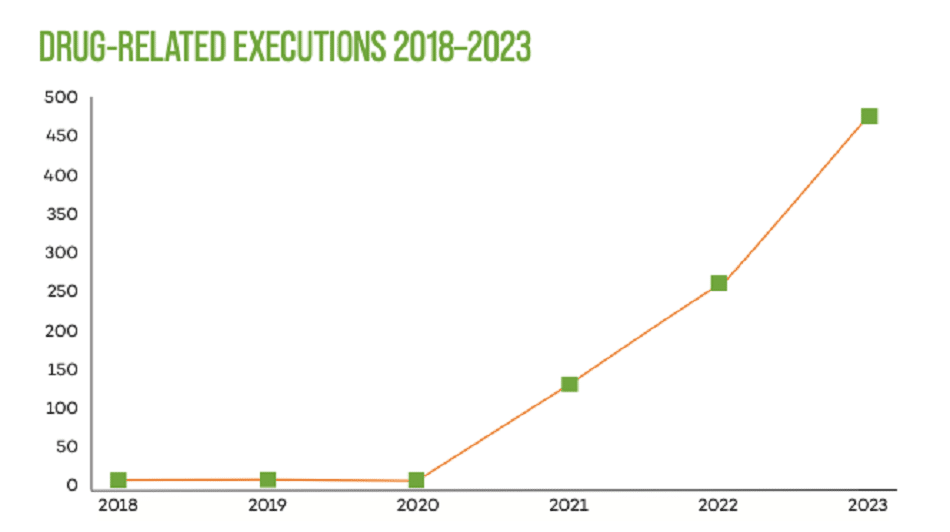

In 2018, we witnessed the most significant decrease in the number of executions in the last decade. Although the number of drug-related executions had the largest reduction, there was also a notable reduction in the number of qisas executions and public executions. It is not known whether the relative reduction in the number of qisas and public executions was a result of a political decision. But there is no doubt that the large reduction in the number of drug-related executions was a direct result of the legislative reforms made in 2017.

"While the number of drug-related executions has dropped significantly since 2015, the number of qisas executions has had fluctuations in both directions. In 2018, both the drug-related and qisas executions had a reduction."

The experience in the past two decades has shown that the international community and the Iranian civil society are the main driving forces behind any reforms towards restricting the use of the death penalty in Iran. The few times we have witnessed policy changes either in law or practice, the authorities have unwillingly given in to the external pressure. The stop in stoning punishment and the recent amendments to the Anti-Narcotic Law are the two processes which will be discussed in the following sections.

How did the practice of stoning as punishment stopped?

After nearly two decades of isolation, with the election of Mohammad Khatami as the President in 1996 the relation the relations between Iran and EU entered a new era. The serious situation of human rights in Iran was an obstacle for the total normalization of EU-Iran relations. Publication of stoning footage by an opposition group[1] received much attention in the international media and was in strong contrast with the reformist image of the new Iranian government. As a condition to upgrade the economic relations the EU put certain human rights demands, including a moratorium on stoning punishment.[2] Iranian authorities informed the EU that a moratorium on stoning had been in effect from the end of 2002.[3] However, the practice of stoning continued secretly and stoning remained in the Iranian Penal code. Human rights activists launched a campaign called “Stop stoning forever” to raise awareness about the continuous practice of stoning.[4] Newly established Iranian human rights NGOs in the diaspora, such as IHR[5], contributed the awareness campaign about the stoning directed towards the European governments.[6] It was first after the massive global campaign for Sakineh Ashtiani [7] which Iran stopped the stoning punishment in practice.

However, the Iranian officials do not appreciate abandoning the implementation of punishments because of the pressure of the international community. In a meeting with the heads of Police on January 15, 2019, Iran’s Chief Prosecutor, Mohammad Jafar Montazeri, said: “I am very sorry that the Islamic Republic has stopped implementing certain hodoud punishment in order to avoid condemnation by the international community”.[8]

Lessons from the process of changing the Anti-Narcotics Law

The first mention of a need for a change in anti-drug legislation came on December 4, 2014, when Javad Larijani, head of the judiciary’s “High Council for Human Rights”, said in an interview with France 24, “no one is happy to see that the number of executions is high.” Javad Larijani continued: “We are crusading to change this law. If we are successful, if the law passes in Parliament, almost 80% of executions will go away. This is big news for us, regardless of Western criticism.”[9] Almost at the same time, the head of the Judiciary, Ayatollah Sadegh Larijani, addressed the need for a change in legislation in a meeting with judiciary officials.

However, nine months earlier in March 2014, the same Javad Larijani had addressed the UN’s “Human Rights Council” about drug-related executions, saying: “We expect the world to be grateful for this great service to humanity”. He continued: “Unfortunately, instead of celebrating Iran, international organizations see the increased number of executions caused by Iran’s assertive confrontation with drugs as a vehicle for human rights attacks on the Islamic Republic of Iran.”[10] This last statement has been the Islamic Republic’s official position for many years.

It is unlikely that the Iranian judiciary has suddenly, in less than nine months, come to recognize the fact that the death penalty does not deter drug crimes.

Iran has used the death penalty for drug crimes since the very beginning of the Islamic Republic in 1979 and both the crime rate and drug abuse has been increasing in the past three decades.

However, international attention on the death penalty for drug offenses is rather new. In recent years, a growing number of global institutions and agencies have expressed public concern about Iran’s use of the death penalty for drug offenses and called for an end to international cooperation with Iranian counter-narcotics efforts. European aid to the United Nations Office for Drugs and Crimes (UNODC) and Iran has been widely criticized.

International NGOs which have urged UNODC to freeze counter-narcotics funding to Iran include Reprieve, Harm Reduction International, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, Iran Human Rights, and Ensemble Contre la Peine de Mort.[11]

Moreover, the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Iran, who was appointed in 2011, has significantly contributed to the sustainable focus on the issue of drug-related executions in Iran. Besides the annual reports where the death penalty in general and the death penalty, in particular, have been addressed, the UN Special Rapporteurs have issued several public statements calling on Iran to abolish the death penalty for drug offences which are not regarded as the “most serious” crimes by the ICCPR which Iran has ratified.

Increasing criticism and awareness led to decisions by individual State donors to withdraw funding from UNODC operations in Iran. In 2013, Denmark withdrew support for such efforts, stating that “donations are leading to executions”[12]. The United Kingdom subsequently did the same, citing “the exact same concerns” as Denmark[13]. Ireland also took similar action with the then Foreign Minister explaining that “we have made it very clear to the UNODC that we could not be party to any funding in relation to where the death penalty is used so liberally and used almost exclusively for drug traffickers”[14].

In October 2015, the European Parliament passed a Resolution with a 569 to 38 majority condemning Iran’s high rate of drug-related executions and calling on the European Commission and Member States “to reaffirm the categorical principle that European aid and assistance, including to UNODC counter-narcotics programs, may not facilitate law enforcement operations that lead to death sentences and the execution of those arrested”.

So, international pressure on the Iranian authorities and thus the increased political costs of continuous executions of drug offenders is most likely the factor which triggered the sudden change in the Iranian authorities’ rhetoric and attitude towards the use of the death penalty. This, in turn, created a space for public debate and encouraged civil society, lawyers and MPs to drive the process of changing the legislation ahead.

Iranian authorities have admitted on several occasions that the political cost of drug-related executions has become too high. In a recent meeting with the General Secretary and other high ranking officers of Iran’s Drug Control Headquarters, the head of the Iranian Parliament, Ali Larijani, said, : ”Death penalty must be the last way of combating the drug problems”, and continued, “the costs of the executions is very high, you must not underestimate the costs”.[15]

It is too early to know whether the change in the Anti-Narcotics Law will lead to a reduction in the number of drug-related executions also in the future. The international community must monitor the process of commuting death sentences closely. Calling for transparency in this process is crucial.

The UNODC, which has been cooperating with the Iranian authorities in fighting drugs, must be given access to the list of all death row prisoners for drug offenses and participate in monitoring and evaluating the process.

The EU and countries which have been funding UNODC projects in Iran must not resume funding until clear results are achieved. Moreover, the issue of due process for drug offenders must be a top priority in future talks with the Iranian authorities.

Strategies to restrict the scope of the death penalty beyond drug offenses in Iran

The examples from the process of stopping the practice of stoning and the change of the Anti-Narcotic Law show that:

– Sustained international pressure is essential

– Creating awareness and mobilization of civil society is very important

At the present moment, putting an end to the execution of juvenile offenders and stopping the practice of public executions seem to be the most reachable goals. Both the international community and the civil society inside Iran are sensitive to these issues. Moreover, Iran is among the very few countries in the world practicing such executions.

Another important step would be to push for legal reforms which promote due process and rule of law. Many of those executed would be saved even within the current Iranian law if the standards for due process of law had been respected by the Iranian authorities. As mentioned earlier in the report, Iran is obliged to the principles of due process and fair trials both through the international conventions it has ratified and its own Constitution.

Changing the qisas law might seem more challenging. Partly because the Iranian authorities consider death sentence for murder (qisas: retribution in kind) as a red line which should not be crossed. The Iranian authorities claim that qisas (retribution in kind) is a private right which the authorities cannot deny or control. On November 11, 2017, following the first round of Iran – EU talks after the nuclear negotiations, Iranian Deputy Foreign Minister Majid Takht-Ravanchi told the Iranian media: “The Islamic Republic of Iran will not cross its red lines, especially regarding capital punishment and qisas (retribution) in human rights talks with the European Union”.[17] Moreover, most of the retentionist countries still practice the death penalty for murder and therefore, it would take longer to establish a broad international consensus around a total abolition for murder cases. However, supporting the abolitionist Iranian civil society might lead to a significant reduction in the number of qisas executions.

References:

[1] http://www.iran-e-azad.org/stoning/women.html

[2] http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/2726009.stm

[3] http://tinyurl.com/y4eodyeb

[4] http://www.wluml.org/action/update-iran-stop-stoning-forever-campaign

[5] https://iranhr.net/en/articles/603/

[6] https://www.nrk.no/urix/store_—steining-stanset-1.2757658

[7] https://iranhr.net/en/articles/460/

[8] https://www.radiofarda.com/a/reducing-violent-punishment-in-iran/29712960.html

[10] http://tn.ai/302871

[11] https://www.hrw.org/news/2014/12/17/un-freeze-funding-iran-counter-narcotics-efforts

[12] The Copenhagen Post, 9 April 2013: Denmark ends Iranian drug crime support

[13] Clegg, Nick, 2013. Writing to Maya Foa of Reprieve. [Letter] (Personal Communication 17 December)

[14] http://www.rte.ie/news/2013/1108/485366-ireland-anti-drug-iran/

Categories

Iran (Islamic Republic of)