The difficult struggle facing Iran’s abolitionists

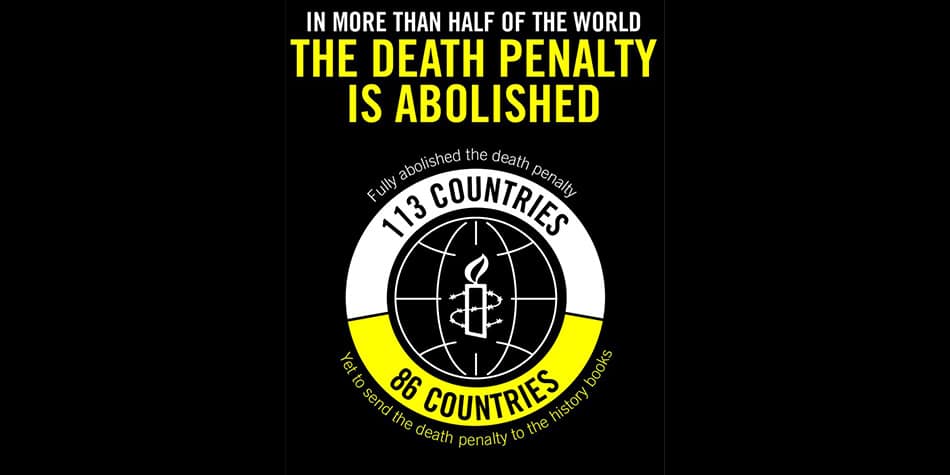

Twenty-one people were hanged in Iran on September 5. This is in addition to the 32 executions that took place there in July and August, according to member organisations of the World Coalition Against the Death Penalty. At least 189 people have been executed since the start of the year. Abolitionists the world over have risen up against this acceleration of killings in the country and their increasingly macabre staging.

The French organisation Together Against the Death Penalty denounced a “bloody summer in Iran”, recalling that the capital, Tehran, witnessed its first public hanging for five years on August 2 , 2007.

Another significant regression was the stoning of a man for adultery on July 5, again the first for five years. The International Federation of Human Rights Leagues recalled on that occasion that “stoning is an inhuman and degrading punishment violating Article 7 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, ratified by the Islamic Republic”.

Along with this wave of executions, the Iranian authorities have also taken care to gag one of the few voices that dares opposing the death penalty in the country. The journalist and writer, Emadeddin Baghi, whose Association for the Right to Life has just joined the World Coalition, has been sentenced to 3 years in prison.

“All this is because of my articles and interviews”, explains Emadeddin Baghi, who has appealed his sentence. All his books are banned and he has already spent three years behind bars.

His sentencing triggered a protest from the French government, which awarded him the French Republic Human Rights Prize in 2005.

Struggling against the secret

In these conditions, how can the death penalty be eradicated in Iran?

Hossein Mahoutiha, a member of the Iranian Human Rights Activist Groups in the EU and Canada, is participating in the struggle from Quebec. For him, returning freely to Iran is out of the question.

“Most of our action is reaction”, he explains. “We defend individual cases, we try to prevent individual executions”.

This work is made difficult by the lack of transparency surrounding death sentences: “We only find out about most executions after the event”, says Hossein Mahoutiha.

Secrecy shrouds the entire procedure as even lawyers cannot speak freely with their clients.

When the Iranian abolitionists learn that prisoners risk capital punishment, they appeal to the international community to act. “When the European Union and others turn up the pressure, things change”, confirms Hossein Mahoutiha. “But in Iran people are divided and there isn’t a big popular movement”.

For example, the repeated criticisms of the international community on the execution of juveniles are starting to have an effect. The Iranian justice system often waits for sentenced juveniles to turn 18 to execute them. “That’s just evasion, the system adapting itself to circumstance”, rues Hossein Mahoutiha.

“The movement is gaining ground”

The Tehran regime, which has presented the wave of executions this summer as a way of “weeding out” unwelcome elements, has managed to maintain a certain amount of popular support for the death penalty in Iran. “If you defend a child rapist, you’re supporting child rapists”, sums up Hossein Mahoutiha.

His organisation has therefore decided not to publish accusations in its reports on the death penalty in Iran, concentrating instead on opposition in principle to capital punishment.

This exiled activist knows that the struggle will be long: “A lack of political will, censorship and the absence of a mass movement mean that our action remains limited”, he recognises.

And yet, there has been progress. “Groups like ours didn’t exist six years ago and the movement is gaining ground. Even I didn’t react in the same way a few years’ ago”, says Hossein Mahoutiha.