Tackling resistance to abolition in Africa

World Congress

Despite a powerful testimony by former Ugandan death row prisoner Edward Mpagi proving that wrongful convictions pose a high risk of executing innocents, Ugandan lawyer Frederick Ssempebwa told the 5th World Congress Against the Death Penalty that his country was trying to widen the scope of the death penalty.

“The bill against homosexuality, which includes the death penalty and is being debated in parliament, is quite a retrograde step,” he said.

One avenue explored by Ugandan abolitionists is to challenge the constitutionality of mandatory sentences, which force judges to apply the death penalty without considering mitigating evidence.

“This could be a big step as many people on death row because of mandatory sentences,” Ssempebwa said.

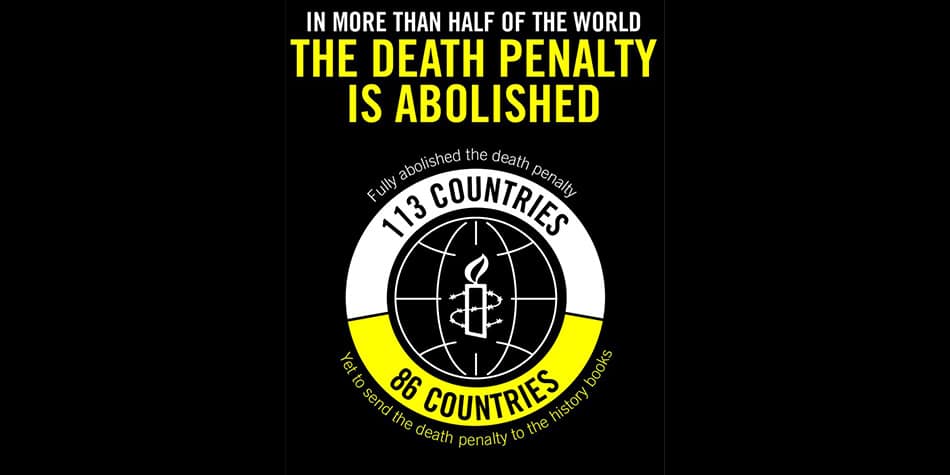

International advocacy and the trend that has seen many African countries abolish the death penalty in the past decade do help Ugandan activists. “Recently, a military court trying a man accused of multiple murders did not apply the death penalty on account of the global initiative to abolish the death penalty. This is very encouraging,” he said.

Religious radicalism in Nigeria

Speaking on behalf of the Nigerian World Coalition member organisation Legal Defence and Assistance Project (LEDAP), Chino Edmund Obiagwu said his country, too, was facing a rising number of capital cases.

Some 12 Nigerian states have introduced Sharia law carrying new capital offences such as adultery and apostasy. “This was done only to attract sympathy from Muslim populations,” Obiagwu said, adding that the death penalty did not exist in African customary law nor in traditional African interpretations of Islam.

Meanwhile, violence linked to the Islamist sect Boko Haram has led the authorities to respond with more capital cases. “The problem is that the definition of terrorism is broad – it includes those who finance it,” he said.

LEDAP has been responding with litigation in the courts and lobbying to call for a moratorium on executions.

“Africans value life and its sacredness,” Obiagwu said. “But when 12,000 people are killed, they become statistics and people don’t value life anymore.”