Executions in Jordan and Pakistan show need to go beyond moratorium

Asia

MENA

In the days following the horrific attack on a school in Peshawar on December 16, 2014, Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif lifted a moratorium on executions and ordered the hanging of four death row prisoners. Meanwhile, Jordan executed eleven convicts for the first time in eight years.

Although Pakistan’s decision officially concerned only cases of terrorism, the authorities have unveiled plans to execute up to 500 people. “At least 200 of them are not terror-related,” the Anti-Death Penalty Asia Network noted. “It is even more disturbing [that] the government is about to execute someone who might have been wrongfully condemned, such as the case of Shafqat Hussain, who was allegedly tortured into confessing to murder and sentenced to death by an anti-terrorism court. He was 14 years old then,” ADPAN added.

The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan denounced the executions as a way of “diverting public opinion”. “HRCP believes that tinkering with the informal moratorium on executions offers no solution to the challenge that Pakistan faces. The flaws in investigation and the overall criminal justice system need immediate attention to ensure certainty of just punishment and not merely quantum of it,” the Commission’s chairperson Zohra Yusuf said in a statement.

Other World Coalition members including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have slammed Pakistan’s decision to lift its moratorium and highlighted the case of Sahfqat Hussain.

Jordan executions unlikely to reduce crime

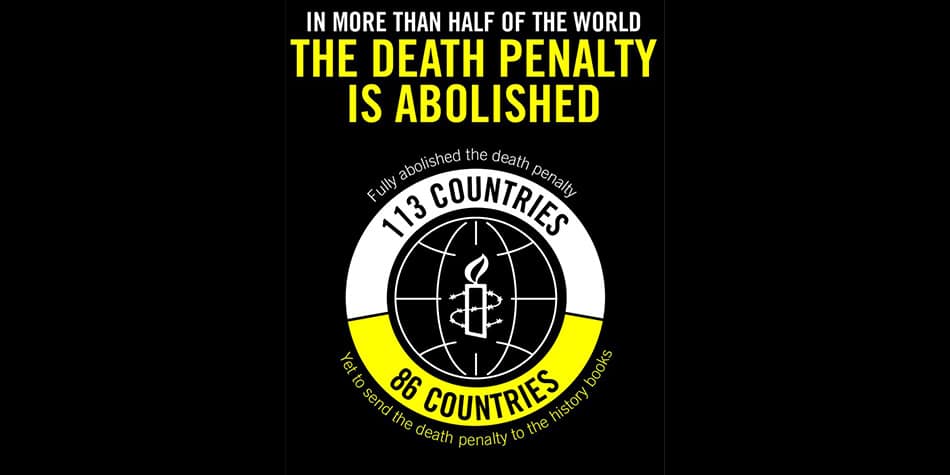

The new UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein urged Pakistan and Jordan to reverse their decisions, which he described as “particularly disappointing given that just last week, a record 117 States voted in the UN General Assembly in favour of an international moratorium on the use of the death penalty”.

The Jordanian government has argued that rising crime rates justified fresh executions.

“The crime rate, historically, is not lowered by the imposition of capital punishment,” Zeid replied. “Instead, shocking cases emerge, with tragic frequency, of the execution of people who are subsequently proven innocent – including in well-functioning legal systems.”

Zeid is a member of the Jordanian royal family and his criticism of the government has caused embarrassment in the country, noted Amman-based Haitham Shibli, the manager of Penal Reform International’s death penalty programme in the Middle East and North Africa. He added that the lifting of the moratorium had spurred Jordan’s civil society and parliamentarians to revive the fight for abolition.

Shibli added that official police statistics link the increase in crime to the recent influx of hundreds of thousands of impoverished refugees from neighbouring Syria – not to the suspension of executions in 2006. “With events around us and radical movements threatening to infiltrate Jordan, the state wanted to send a message that it is strong and will do whatever it takes to ensure stability,” he said.

World Coalition president Florence Bellivier said the recent executions in Jordan and Pakistan illustrated the fragility of moratoria in the face of political circumstances. “In cases of instability or in the run-up to elections, a moratorium can always be reversed. That is why abolitionists see it as a first step, but cannot be satisfied by it,” she said.

Only full abolition of the death penalty can ensure the certainty that is required of penal law, she added.