Algeria: it’s time to move from the moratorium to the abolition

MENA

The rule of law at the core of the discussions

What stands out of the different interventions is the desire to link the issue of the death penalty to the rule of law. The participants referred many times to the judicial independence and to the use of the death penalty against political opponents.

It is in this context that M. Mustapha Bouchachi, an Algerian lawyer, insisted on the lack of independence of the judicial system and on the discriminatory character of the use of the death penalty. He recalled that between 1962 (independence of Algeria) and 1993 (institution of an official moratorium on the executions), the 33 executed persons were poor or political opponents. He then referred to the “fake democracy” adding that in Algeria 99% of the bills don’t even pass through the Parliament. This lack of independence is aggravated by the lack of resources that the State provides to the judge in order to carry out investigations: for example, it is only recently that it is possible for investigators to collect fingerprints on the crime scene.

The death penalty, a political issue

Describing it as linked to the political context but also as a repressive tool, the participants addressed the death penalty trough a political perspective. It is in this lights that Ali Haroun, lawyer, former Vice-Minister for Human Rights and former member of the High State Committee, referred to the moratorium as the “Sword of Damocles” which would throne over the political opponents. This expression highlights the political choice of the regime to not abolish the death penalty in Algeria.

This was also stressed by Abdennour Benanter, a professor of the University of Paris 8, who considers that the abolition of the death penalty shouldn’t be subjected to the consent of the population, as the government doesn’t ask for its opinion for other political issues.

Meanwhile, Florence Bellivier, deputy Secretary General of the FIDH, reverted to the death penalty and political violence, taking the case of terrorism as an example. She recalled that terrorism and the abolition of the death penalty aren’t a good combination, since even though the death penalty is by no means dissuasive, especially in the case of terrorists who are generally not afraid of dying, States use the fight against terrorism as a pretext to revive the use of the capital punishment.

A moratorium to “stop the bloodshed”

While asserting that the Algerian society isn’t ready to abolish the death penalty, the President of the National Union of the Algerian Bar associations Ahmed Saï, stated that it is necessary to analyze the death penalty in an objective way. To this regard, he recommends backing away from the context of the commission of the crimes and not to focus exclusively on legal arguments. Indeed, crime and more specifically child abductions are more and more frequent in Algeria. This strengthened the arguments of the ones in favor of the death penalty. Ahmed Saï, however, welcomed the reduction of the scope of the death penalty since 1993.

Miloud Brahimi, an Alger bar lawyer, explained that the moratorium of 1993 was decided in the context of an internal crisis, the black decade, with the objective of “stopping the bloodshed”. He also underlined that on June 26th, 2004, a bill for the abolition of the death penalty was summited by the Ministry of Justice but it was never presented to the Parliament. This seems surprising when we know that Algeria often votes in favor of the resolution of the General Assembly of the United Nations calling for a moratorium on the death penalty.

Abdelgahni Meziani, President of the Court of Rouiba, also took the floor and affirmed that, in his opinion, the death penalty “is a matter of revenge and is closer to lynching”. This intervention was surprising as it’s not often that active sitting judge expresses himself so freely about the death penalty.

The presentation of Tareq Zouhair, a lawyer from the Casablanca bar association, highlighted a strong paradox. Indeed, he recalled that therapeutic abortion and euthanasia are forbidden in Algeria on behalf of the right to life while it is this same right that is largely scorned by keeping the death penalty in the Algerian and Moroccan legislations.

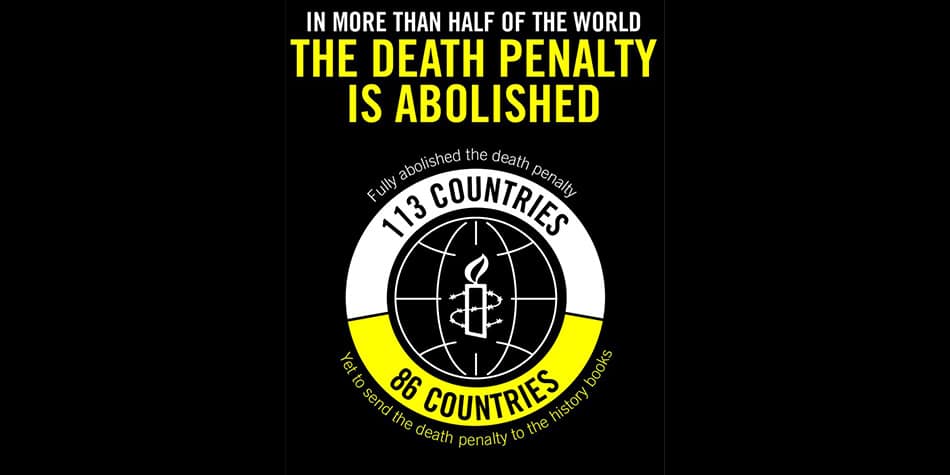

The conclusion which stood out of this very interesting seminar is that it’s time for Algeria, as for its Moroccan neighbor, to pass from the moratorium on the executions to the total abolition of the capital punishment.