Between hope and disillusion: the Iranian death penalty reform

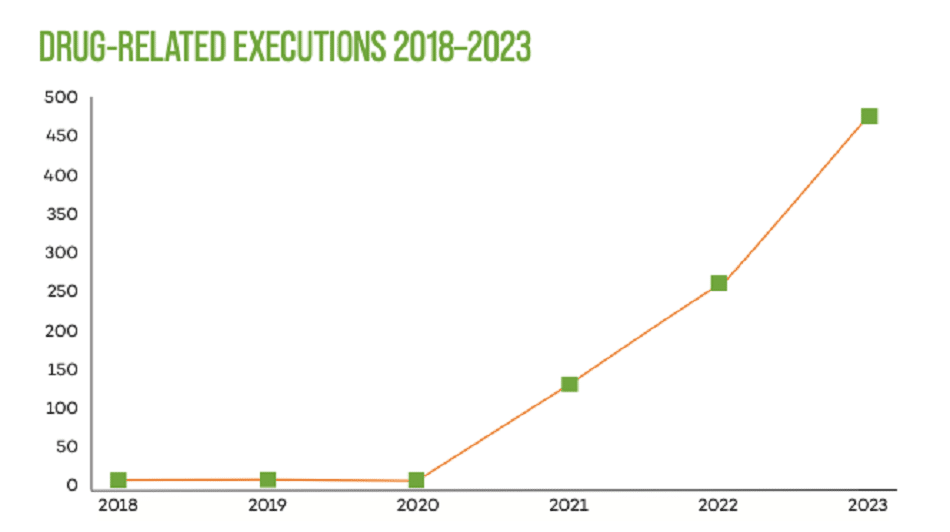

With more than 567 executions in 2016, Iran is one of the leading countries in terms of death sentences and executions. In a country where most of death sentences are issued for drug offenses, this bill has appeared as an opportunity to overturn these infamous statistics.

A potential drop in the number of executions

On December 2015, members of the Iranian Parliament brought a bill to eliminate the death penalty for 16 of the 17 drug offenses criminalized under the Iranian’s anti-narcotics law. Thrilled by this proposal that could reduce the execution rate by 80%, Amnesty urged the Iranian Parliament not to “squander the opportunity to end executions for drug related offenses.” Under the former version of the law, mandatory death penalty was mandated for drug trafficking, but not only. Indeed, possessing more than 30 grams of synthetic drugs was enough to be convicted and sent to the gallows. Even though the death penalty would have still applied to leaders of drug trafficking cartels or anyone using children in drug trafficking, the original version of the amendment sought to replace capital punishment with imprisonment for up to 30 years.

According to Sarah Leah Whitson, Middle East director at Human Rights Watch, the amendment could have saved “hundreds of people from execution who never should have been on death row in the first place.” The interruption of executions since the beginning of Ramadan in Ghezelhesar and Karaj Central prisons raised great hopes among the international community. Unfortunately, the 39 executions of prisoners convicted on drug-related charges quickly destroyed all expectations. Abolitionists urged the Iranian authorities to suspend executions of drug offenders until parliament could vote the bill.

“A deeply disappointing piece of legislation”

Whereas Iranian authorities have recognized the absence of deterrence effect with regard to the death penalty and drug offences, the amendment has not substantially reformed the former legislation. By narrowing the scope of the bill, the Iranian lawmakers deprived the bill of its original purpose. “Instead of abolishing the death penalty for drug-related offences, the Iranian authorities are preparing to adopt a deeply disappointing piece of legislation,” said Magdalena Mughrabi, Deputy Director for the Middle East and North Africa at Amnesty International.

Despite the replacement of the death penalty by a 30 years’ imprisonment sentence for drug related offenses, the parliament, under the pressure of the Iran’s judiciary and the Interior Ministry’s drug control headquarters, has finally maintained capital punishment for non-violent charges of “production, distribution, trafficking and selling drugs”. In July 2017, the parliamentary commission even restored the death penalty for “possession, purchase or concealing” of 50 kilograms of “traditional drugs”. In a joined statement with Amnesty International, Roya Boroumand, Executive Director of Abdorrahman Boroumand Foundation, held that “the choice between life or death should not come down to a crude mathematical calculation based on a quantity of drugs seized from an individual.”

Whereas the World Coalition Against the Death Penalty is about to launch the 15th World Day against the death penalty with a focus on poverty and justice, the Abdorrahman Boroumand Foundation has recalled that most of the executed come from poor and vulnerable backgrounds. For Human Rights Watch, the situation is worsened by the serious violations of due process, torture and other violations of the rights of people charged of drug offenses. Disappointed by the amendment, Amnesty International and the Abdorrahman Boroumand Foundation have called on the international community to “urge Iran to amend the bill to abolish the death penalty for all drug-related offences. The Iranian authorities must move towards a criminal justice system that is focused on rehabilitation and treats prisoners humanely.”