Reorienting Drug Policy in Indonesia towards the Achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals

In their latest published report, LHB Masyarakat, Reprieve, and the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs shed light on the lack of coherence between Indonesia’s national campaign to eradicate illicit drugs and its firm commitment to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

In September 2015, member states of the United Nations adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, with Indonesia as one of the key actors that helped formulate its framework and pursue its adoption at the global level. Apart from this, the country also aligned an ambitious 5-year development program with the SDGs and sought out numerous efforts to improve the quality of life and upgrade its public health and social welfare infrastructure. True to the SDGs, Indonesia focused on those who are “left behind” by putting an emphasis on the development of the welfare of poorer citizens and those living in remote regions.

However, despite its commitment to the SDGs, Indonesia uses a strategy against illicit drugs that has impeded development, fueled poverty, aggravated inequalities, and caused more harm to citizens than over the drugs it has tried to control. A law passed in 1976 adopted strict penalties for drug offences, including the death penalty, and a basic rehabilitation framework, which faces significant challenges in implementation at present. The current Long-Term National Development Plan (RPJPN) 2020-2024 frames illicit drugs as a threat to national security but has largely ignored the socioeconomic implications of having punitive drug control measures in place, and has also failed to couple such measures with investments in evidence-based health and social services.

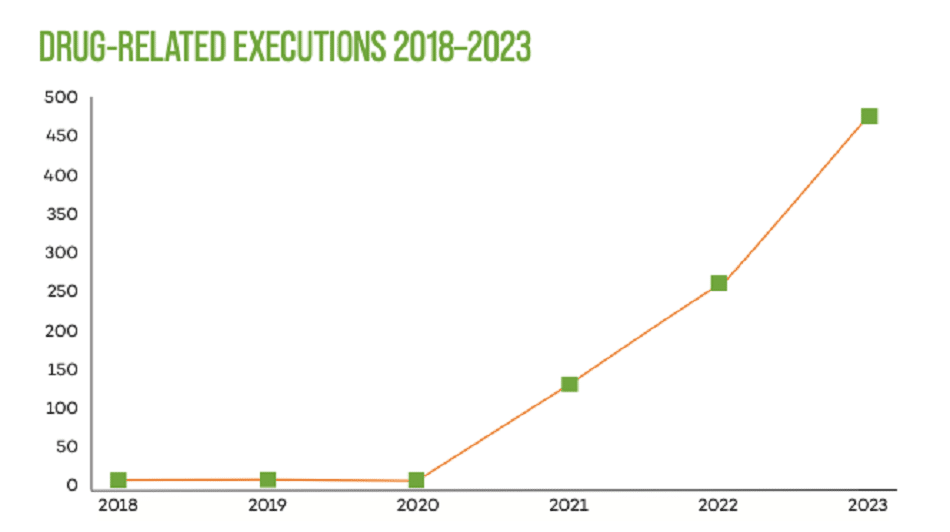

As a result, despite the considerable cost of the drug control strategy in Indonesia, levels of drug availability and use have been at an all-time high. Drug control efforts have led to numerous problems in the country’s penal system, including overcrowding in prisons, the poor provision of health services and rehabilitation programs, and the disproportionate handing of the death penalty for offenders. The number of individuals sentenced with the death penalty in relation to drug-related offenses has increased in the years after the adoption of the 2030 Agenda, running contrary to the SDGs’ aims to uphold the right to life, decrease violence, and protect fundamental freedoms, and uphold a peaceful and just society.

Furthermore, individuals who are punished for drug use are unable to pay for legal services and are more likely to be deprived of access to justice. In 2015, out of 42 death penalty cases, 11 defendants were deprived of legal counsel in the police investigation and court proceedings. The ones who are “left behind” – those who are poor, vulnerable, mentally impaired, or subject to discrimination due to their skin – are disproportionately given the death sentence, many of which are arbitrarily handed down and are based on unreliable data and assumptions that are not borne out of evidence.

The SDGs cannot be achieved when national policies enable injustice, fuel violence, drive poverty and inequality, and stigmatize disadvantaged groups. Drug policies must not undermine the SDGs but instead contribute to their achievement. With only ten years left to fulfill the 2030 Agenda, Indonesia should take the opportunity to reaffirm its commitment to the SDGs by abolishing the death penalty and adopting a fair, well-rounded, and human rights-based approach to its pervasive drug problem.