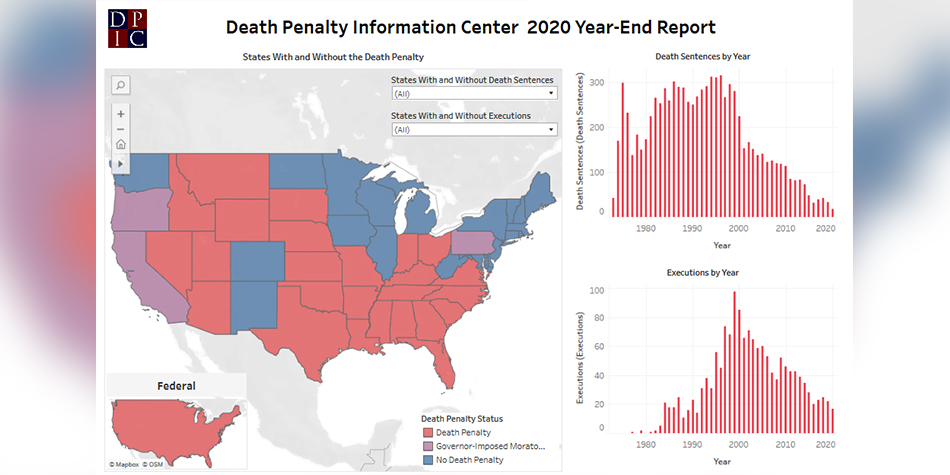

DPIC’s Report on the 2020 Death Penalty Usage in the US

Statistics

TheDeath Penalty Information Center’s 2020 annual report highlights the continuing trend toward abolition in the US and the resumption of federal executions in a challenging COVID-19 context.

The Death Penalty Information Center’s year-end report highlights the use of the death penalty in the US and the continuing trend towards abolition over the past year, whether it be in law or in practice. While capital punishment lost ground among the US States in 2020, following the abolition in Colorado and a new legislation aiming to further limit the use of the death penalty in California, this year was marked by the historically deadly resumption of federal executions after a 17-year hiatus. The report also emphasizes persisting biases in the application of capital punishment in the US, including over the recent federal executions, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the administration of capital punishment.

A Continuing Decline of the States-Conducted Death Penalty

On 23 March 2020, Colorado became the 22nd US States to abolish the death penalty for all crimes after Governor Jared Polis signed a legislation in this regard and commuted sentences of the remaining three State’s death row prisoners to life in prison. “[T]he death penalty cannot be, and never has been, administered equitably in the State of Colorado.” Governor Jared Polis stated when announcing the commutations. Two thirds of the US States have now either abolished the death penalty in law or not carried out executions in at least 10 years – in 2020, Louisiana and Utah both marked ten years with no execution, which means 12 States have been observing a 10-year de facto moratorium on executions across the United States.

California’s legislature also passed a bill aiming to limit the use of the death penalty and address racial biases within capital proceedings. These reforms shall allow capital defendants to resort to statistical evidence of racial bias in order to challenge their sentences, and should contribute to expanding the ban of the death penalty for intellectually disabled people. However, with 724 people awaiting execution in 2020, California remained the State with the largest death row population in the US.

A total of 2,591 people was known to be under sentence of death in the US in 2020, and 5 people were exonerated due to prosecutorial misconducts after they spent between 14 and 37 years awaiting execution. The number of new death sentences plunged this year to a record low of 18 due to the COVID-19 pandemic which artificially contributed to this historic drop, as it prompted most courts to delay trials. A total of 5 States conducted 7 executions over the past year, carrying out 15 fewer executions than in 2019 – namely Alabama, Georgia, Missouri, Tennessee, and Texas. Yet, the use of the death penalty in the US still results in many violations of defendants’ basic rights. Death sentences continue to be disproportionally applied to the most vulnerable citizens, including emotionally, intellectually or mentally disabled people, and 3 of those who were executed in 2020 were known to be 18 years of age at the time of the offense.

Recent Federal Executions Killed More People Than All States Combined

The Trump Administration resumed federal executions on 14 July 2020 after a 17-year hiatus and carried out, in roughly half a year, 10 out of the 17 executions conducted across the United States in 2020 (59%). For the first time in American history, the number of executions authorized by the federal government exceeded the number of executions recorded by all States combined, as well as the number of executions approved by any prior administration. “The sheer number of executions set the Trump administration apart as an outlier in the use of capital punishment”, the DPIC’s annual report argues.

Federal executions reflected many problems in the application of the death penalty, such as Lezmond Mitchell’s case, the second federal death row prisoner to be executed under the Trump Administration. Mitchell was the first Native American ever executed by the federal government for a murder committed on tribal lands. His execution therefore raised significant questions on the respect for Native American sovereignty over criminal matters, since the Navajo Nation has long opposed the death penalty it considered inconsistent with its culture. The “highly politicized” spree of federal executions has been raising additional ethical issues as they included the first federal executions of teenaged offenders in almost 70 years, the first federal execution in almost 60 years for a crime committed in a State that has abolished capital punishment, and the first lame-duck federal execution performed in more than a century. The outgoing Trump Administration has continued to schedule new executions after losing to President-Elect Joe Biden, such as Lisa Montgomery’s, who could be the first female federal death row executed since 1953.

How the COVID-19 Pandemic Has Impacted the Administration of the Death Penalty

The COVID-19 pandemic has not only affected the daily life of millions American citizens but also disturbed the administration of the death penalty, leading to a remarkable decrease in the number of new death sentences and of executions. “[T]he budget strain caused by the pandemic and the need for courtroom space to conduct backlogged non-capital trials and maintaining a functioning court system may force states to reconsider the value and viability of pursuing expensive capital trials.” Yet, the resumption of federal executions in July 2020 forced lawyers, victim’s families, and others to travel to prison facilities, putting them at high risk of being infected – such as Lisa Montgomery’s attorneys –, which is likely to have sparked local outbreaks.

At least 14 executions were delayed because of the pandemic and only Missouri, Texas and the federal government carried out executions after the pandemic reached the US – no State did so after 8 July 2020. According to the Death Penalty Information Center, courts shutdowns played “a significant role” in the number of executions reaching their lowest level in 37 years. “The numbers will remain artificially low until the pandemic subsides, as court closures and continuances delay death penalty trials and push back death warrants and executions” the report asserts.

Read the full report here.

Categories

United States