Over 8,000 people on death row in South Asia

Asia

With few executions but one of the biggest death rows in the world, South Asia is at a crossroad. Recent publications explore mental health on death row and social and economic background of people sentenced to death in Bangladesh, India, the Maldives, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

The population of South Asia is about 1.787 billion or about one-fourth of the world’s population. But the death row population is over one-fourth of the world’s population on death row. 8,186 people are believed to be under a death sentence in South Asia (2,600 in Bangladesh, 488 in India, 22 in the Maldives, 3,831 in Pakistan and 1,239 in Sri Lanka, with at least 86 women). Executions are sporadic. Bangladesh executed 2 people in 2022 https://deathpenaltyworldwide.org/, India executed 4 people in 2020, Pakistan 14 in 2019 and there have been no executions in the Maldives and Sri Lanka for over 40 years.

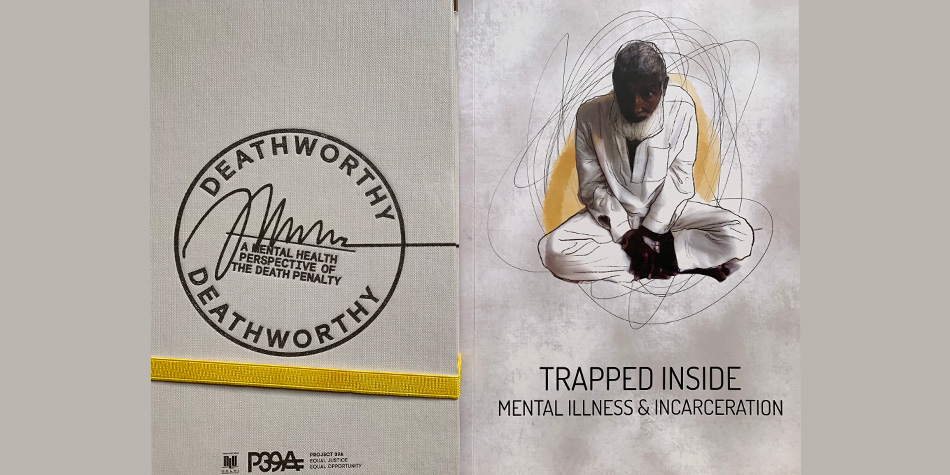

Death Worthy

This report on a mental health perspective of the death penalty in India was published recently by Project 39A. They interviewed 88 death row prisoners (3 female, 85 male) and 110 families across seven states. They took a biosocial approach to mental health and looked at the vulnerabilities and the social reality of death row prisoners, not just their medical records or psychiatry evaluations.

Their findings are appalling: 51 death row prisoners (62.2%) were diagnosed with at least one mental illness.

Among the 88 prisoners interviewed, the cascading effect of poverty was clear. 46 prisoners were physically or verbally abused as children, 64 were neglected, and 73 prisoners grew up in disturbed family environments. 46 prisoners had less than 10 years of education, 28 had early onset of substance abuse. 73 prisoners had experienced 3 or more adverse childhood experiences.

34 (over 50%) out of the 63 prisoners who volunteered information on suicidal behaviour and ideation spoke about contemplating suicide at least once in prison. 8 prisoners had attempted suicide in prison. These numbers and proportion are alarmingly high when compared to the proportion of those at high risk of suicide among the general prison population (4-6%) and in the community (0.9%). 94.1% of the prisoners at risk of suicide, also reported death row distress.

9 out of 83 death row prisoners (approximately 11%) were diagnosed with intellectual disability. While international law prohibits imposition of the death sentence on persons with intellectual disabilities, in the case of these nine prisoners, their disability was not even brought to the attention of the courts.

The report also speaks about the pains of death row and the impact on the families of death row prisoners.

Trapped Inside

This report on mental health on death row in Pakistan was published by the Justice Project Pakistan early 2022. It reflects on the landmark Supreme Court judgement in the case of Safia Bano and Others v. The State on 10 February 2021, when the Supreme Court of Pakistan established key safeguards for mentally ill defendants on death row, reiterated and upheld protections that must be afforded to persons with psychosocial disabilities at every stage of the criminal justice system. In practice, however, these standards for the trial and sentencing of mentally ill defendants are seldom applied.

Pakistan’s criminal justice system overwhelmingly fails to offer adequate protection during arrest, trial, sentencing and even during detention for those suffering from mental illness. The lack of mental health treatment and training means that many individuals never get diagnosed and mental impairment often goes undetected prior to the commission of the offence and at trial. The majority of mentally ill defendants thus obtain their first diagnosis of mental impairment after incarceration.

Moreover, the practice of separating mentally ill persons by holding them in protective custody, usually in a single cell, excludes them from equal participation in prison life. It reduces their access to education and recreational activities which may further deteriorate the psychological welfare/mental wellbeing of the prisoners. Therefore, the legal provisions segregating mentally ill persons must be amended to ensure that they are exposed to meaningful human contact, so that placing them in protective custody does not amount to solitary confinement.

Living under a sentence of death

In a recent study published by the Department of Law, University of Dhaka in collaboration with the Bangladesh Legal Aid and Services Trust (BLAST) and The Death Penalty Project, relied on interviews with family members of 39 death sentenced prisoners, and on primary case records to chart the progress of cases in the High Court Division.

All but one of the prisoners for which data were gathered in Bangladesh were men. Most had been relatively young at the time of the offence, which could suggest a high potential for reformation as well as lower culpability, yet these young people had been sentenced to death. High educational attainment is a protective factor in many social, economic and legal matters. Not surprisingly, like the Indian prisoners, most were not educated to a high level and, partly in consequence, most were economically vulnerable: low-paid employees or unemployed. Notwithstanding their somewhat precarious financial positions, more than half of the families secured private legal representation for the defendant during the trial. This finding may be surprising, but it replicates the data gathered in India. Clearly, in both jurisdictions, faith in legal aid lawyers is low.

According to ODHIKAR Human Rights Report 2021: “Every year a large number of accused persons are being sentenced to death in the lower courts. Death reference cases from different districts of the country are constantly being submitted to the Death Reference Branch of the High Court Division of the Supreme Court. The huge backlog of cases means that innumerable accused persons have been imprisoned in solitary confinement (condemned cell) across the country for years. It is to be noted that most of the victims are poor, less educated and underprivileged.”

Mental health issues faced by condemned prisoners in Sri Lanka

In a prison study published by Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka in 2020 also reflects on the mental health of death row prisoners.

Studies have shown that protracted periods spent on death row in confinement can make inmates suicidal, delusional and insane, which is also reflected in the data gathered during this study. 78% of male and 33% of female condemned prisoners stated that feelings of anxiety, depression and sadness interfere with their daily functioning. In addition, 12% of male and 6% of female condemned respondents stated they have self-harmed, while a statistically significant number of male condemned prisoners stated that they have thought about committing suicide. 9% of male condemned prisoners and 10% of female condemned prisoners stated that they have attempted to commit suicide while in prison.

Qualitative data gathered during the study indicates that prisoners on death row are suffering from the death row phenomenon. Possible experiences of the death row phenomenon/syndrome are described by condemned prisoners in the study as follows:

“I never go out for the exercise time, for about five years. I used to go to the mosque on Friday earlier but since the last three to four years I don’t go to the mosque either. I didn’t even go there during fasting time. If I go, they will ask me: why did you not appeal, they will ask about my case, they will talk about how the other two [co-defendants] got a re trial from the Court of Appeal. Even when going to the mosque, people talk about these things. It is very depressing to talk about these things, so why should I go? I’m not involved in any prison activity or rehabilitation program or classes, there is no point. There is no purpose in going out [of the ward]. I just keep to myself. My family used to come for open visits earlier. They don’t come anymore. I only call them about two to three times a year from the phone booth. I don’t know what to say to them. If I call them, I have to tell them something and they will ask questions. When are you coming home? I don’t have any answers. So,to make everyone’s lives easier, I don’t talk to them. What’s the point of being in pain and sadness every day? In addition, giving that pain and sadness to people at home? If there is no solution, there is no point in discussing the problems that exist. I am on medication for a mental illness. In 2017 it got severe and they sent me to PH.”